In 1943, her husband suggested that she make a good will trip to the other war front, the Pacific. This was not the only trip she took into a dangerous war zone. After much discussion the President said, “I don’t care how you send her home, just send her.” Ambassador and British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, felt a commercial aircraft would be dangerous for her as well as her fellow passengers, should the Germans discover she was on a specific flight. The President did not want her to take a military plane and the U.S. Roosevelt to travel home, the question of how she should make the trip became an issue. She wrote, “These British Isles, which we always regarded as class-conscious, as a place where people were so nearly frozen in their classes that they rarely moved from one to the other, became welded together by war into a closely knit community in which many of the old distinctions lost their point and from which new values emerged.” Doubtless she was hoping this kind of positive change could eventually occur in the United States with respect to racial differences. She also felt that the effort to win the war erased the lines of social class among the British citizens. Roosevelt was impressed with all the work women did to support their country. She walked me off my feet.” During the course of her travels, Mrs. One reporter wrote, “She walked 50 miles through factories, clubs and hospitals. At one point she even inspected a parachute battalion and insisted on having the pilots help her into the seat of a cockpit of a plane. There was nothing that she did not want to see and experience. She collected hundreds of names and followed through on her promise. She spent time with hundreds of wounded servicemen and offered to write to their families when she returned home. She visited clothing distribution centers, military and naval bases. Each day included writing a My Day column. While touring England, Eleanor Roosevelt’s typical day began at 8:00 AM and ended at midnight.

People who officially accompanied her were dubbed “Rover’s Rangers”.

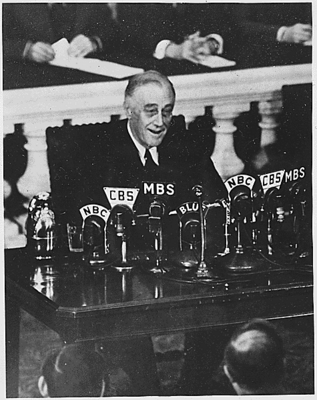

ROOSEVELT DAY OF INFAMY SPEECH CODE

Although the Secret Service assigned her that code name, she suspected that her husband had something to do with the choice. Instead she was given the code name “Rover”.

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-tbt.s3.amazonaws.com/public/TUHMFHWGQII6TCHRIBWI6S7HAY.jpg)

Therefore, her name was not mentioned in official communications. Security and secrecy were essential to ensure the safety of the First Lady. Despite the danger, Eleanor Roosevelt was determined to go because she wanted to be doing something useful. When FDR approached her about taking a trip to England to observe the women’s role in the war effort and visit American servicemen, she was delighted.īy October of 1942, Eleanor Roosevelt was on her way to visit a country in the midst of war, where the shrill sounds of air raid sirens and the whistle of German bombs were a part of daily life. In later years, she wrote, “In retrospect, the thing that strikes me about these days is my triple barreled effort to work with the Office of Civilian Defense, carry out my official engagements and still keep the home fires burning.” I wonder particularly how I ever managed to get in all the trips I took.” Yet at the time, she felt that she was not doing enough. Her “My Day” columns were filled with information about the efforts to prepare for the war on the home front, and seeking to rally citizens to do their part by volunteering for organizations like the Red Cross. Then she was off to the west coast, travelling to Oregon and San Francisco to help organize Offices of Civilian Defense in that area. That evening, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt gave a radio address about the need for Americans to focus on the war effort, trying to calm fears for the future, and calling upon women and young people for their support of the President and the nation’s leaders in the difficult days ahead. On December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered his “Day Of Infamy Speech”. Harmon and Admiral Chester Nimitz pose with the Eleanor Roosevelt in front an Army Air Force C-47 bearing her name during a stop on New Caledonia, September 14, 1943.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)